USABILITY STUDY AT CONVOY

Evaluating an internal product at launch and demonstrating the value of usability studies and behavioral user data

Note: Please reach out if you would like to see a specific artifact like a study plan. These are only available by request.

An Opportunity for a Usability Study

When I joined the product team, they were ready to roll out a new internal product to Convoy Account Managers. The team had already received feedback from a group of beta users. I offered to conduct a usability study to increase the rigor of the existing feedback and to evangelize the value that evaluative UX research can bring to the product design process.

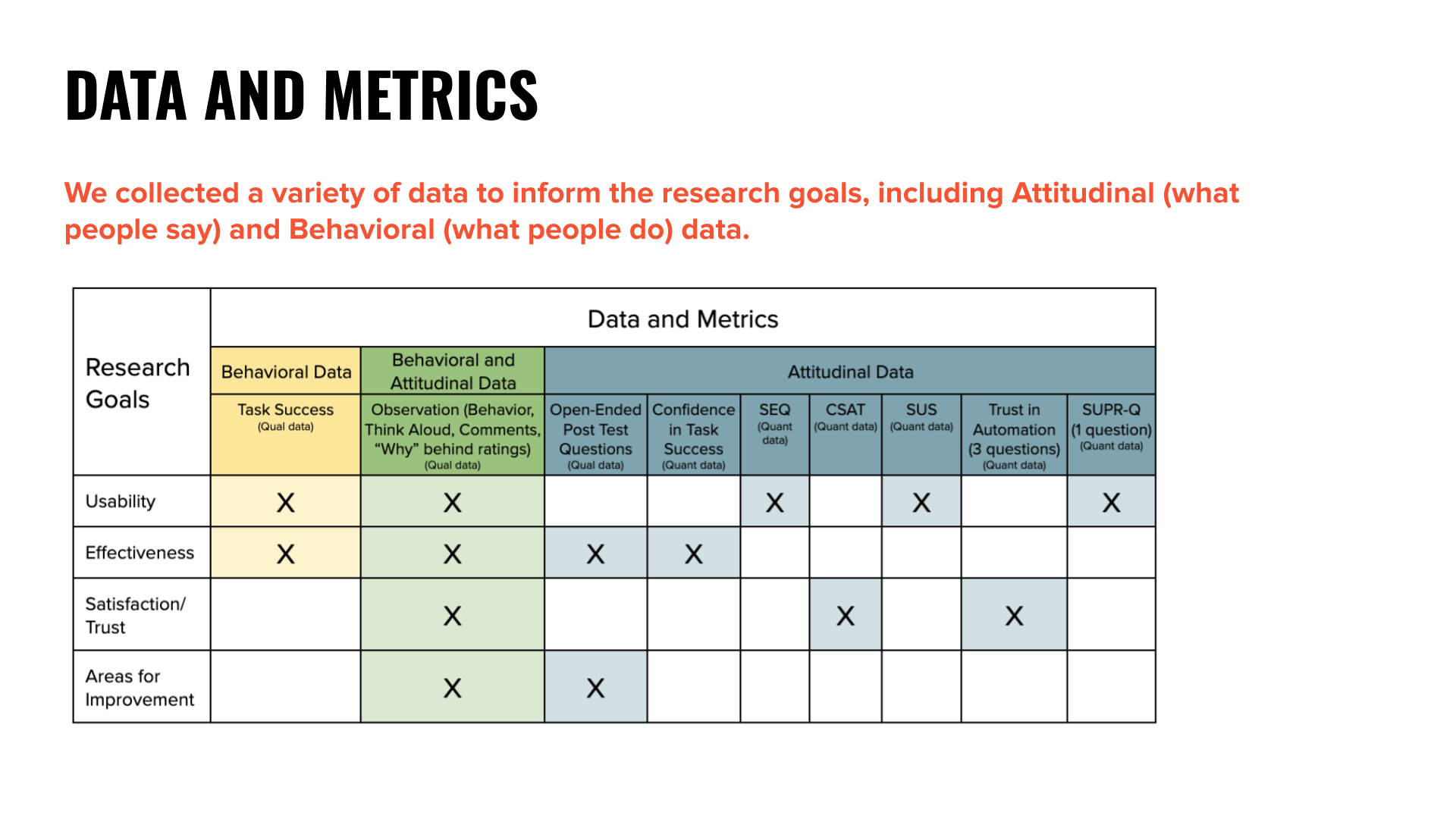

Study Goals and Data to Collect

I set out to measure usability, effectiveness, satisfaction/trust in the product, and to find opportunities for improvement. I planned to collect several types of qualitative and quantitative data, and I mapped each type of data to the study goal it supported. The measurements would be a useful baseline, as the same study could be repeated in the future.

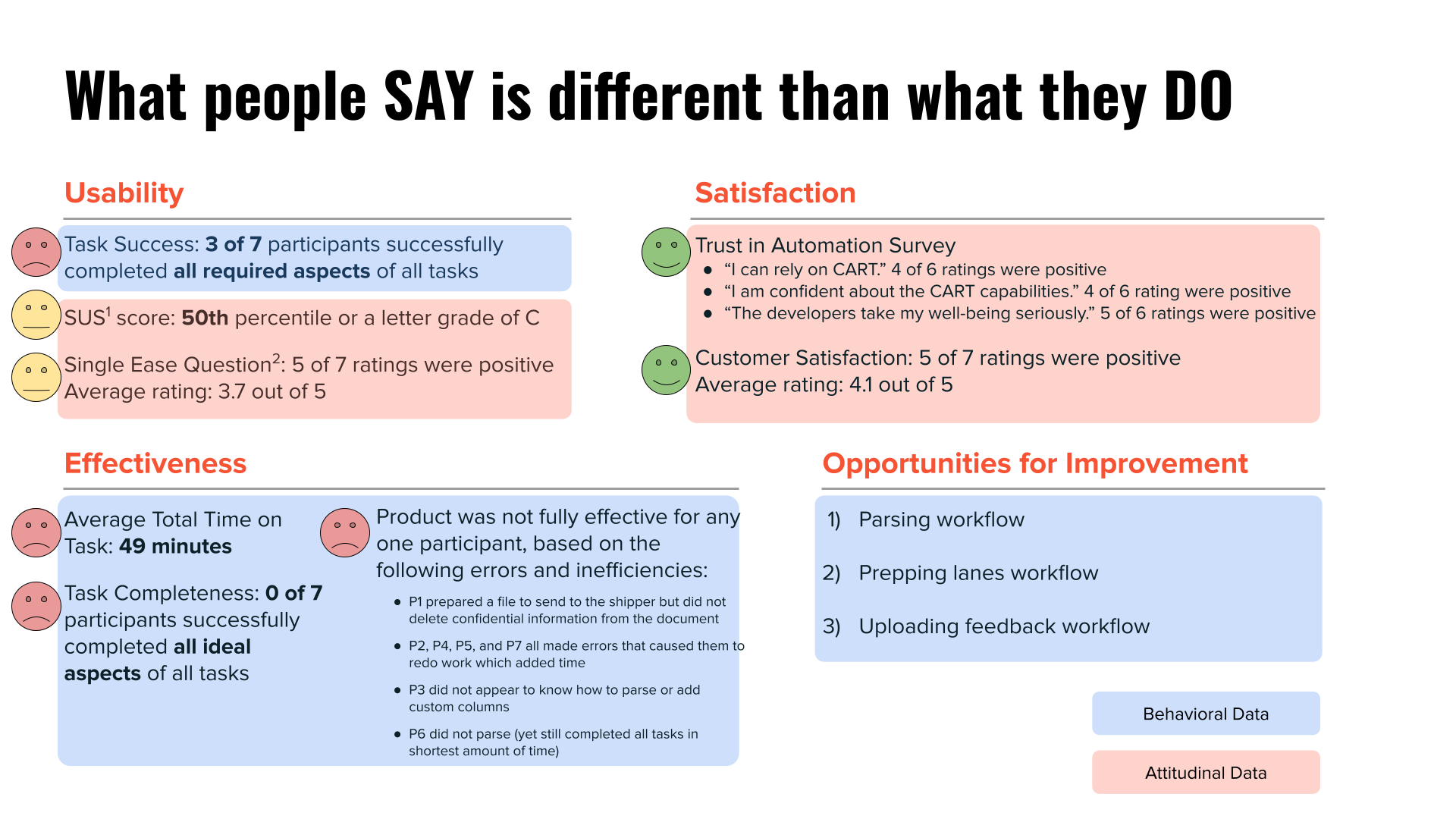

One of the UX principles I always keep in mind is, “What people say is different than what they do.” The team already had a good idea of what users would say based on feedback from the beta group, so I especially wanted to provide a product perspective based on behavioral data and explore similarities and differences in the results based on behavioral and attitudinal data.

Study Execution and Insights

Despite having a detailed study plan and making changes based on a pilot session, I also needed to make adjustments during the study. These study “hiccups” turned out to be clues pointing to some of the most important learnings.

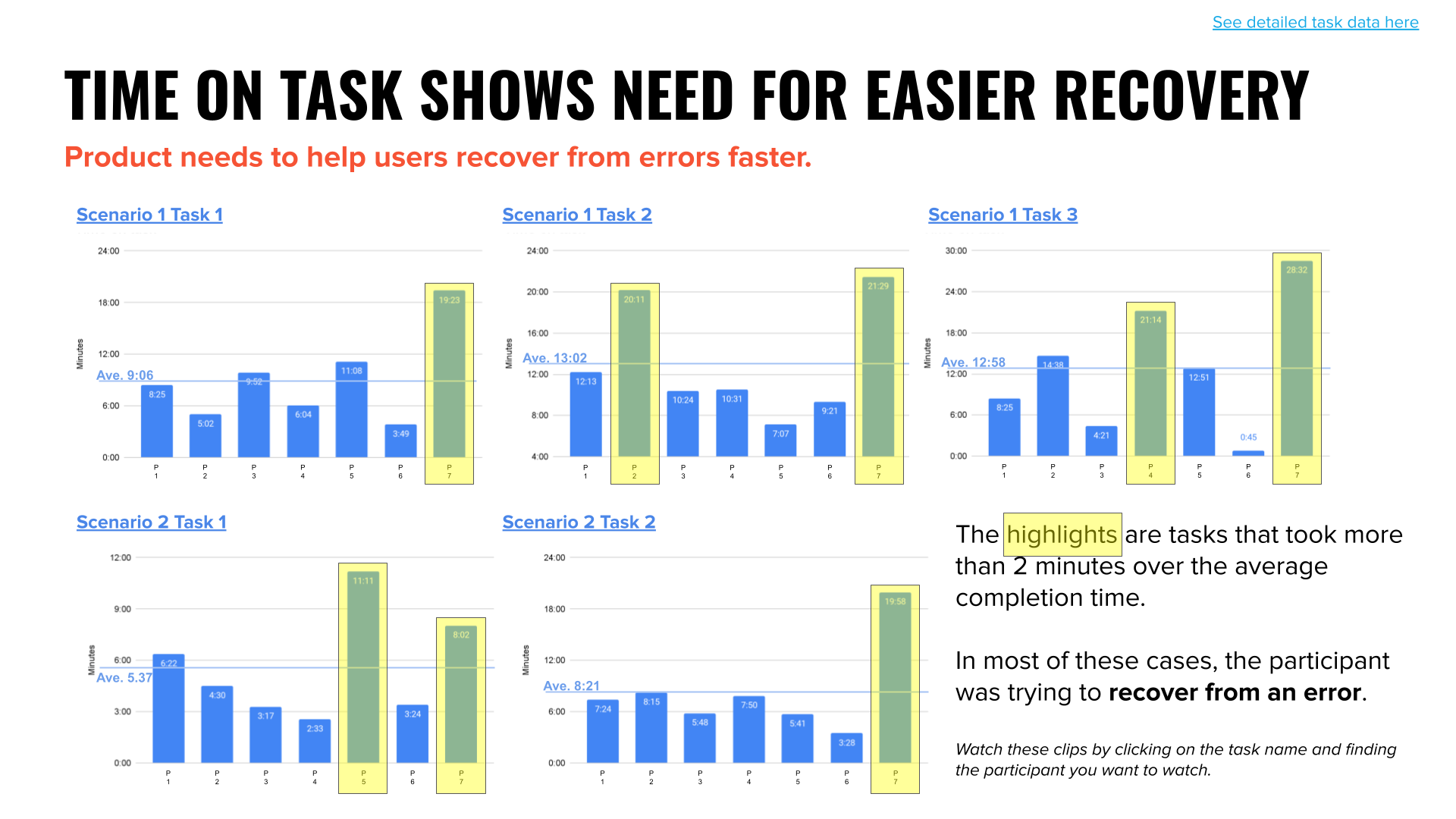

Time was an Important Factor

In the first two sessions, I ran out of time with the participants. I didn’t catch this need for a longer session while running the pilot because all the tasks went smoothly. In contrast, sessions one and two went overtime because whenever the participant made an “error” it took a lot of time to get back on track. This was an important pattern which led me to retroactively measure time-on-task by reviewing recordings. While not a rigorous measurement, it brought attention to a high-level issue with the product. The product wasn’t forgiving of user’s errors. It needed to be better at helping users correct or recover from an error. This finding became one of three principles I presented to the product team to help them frame future product opportunities.

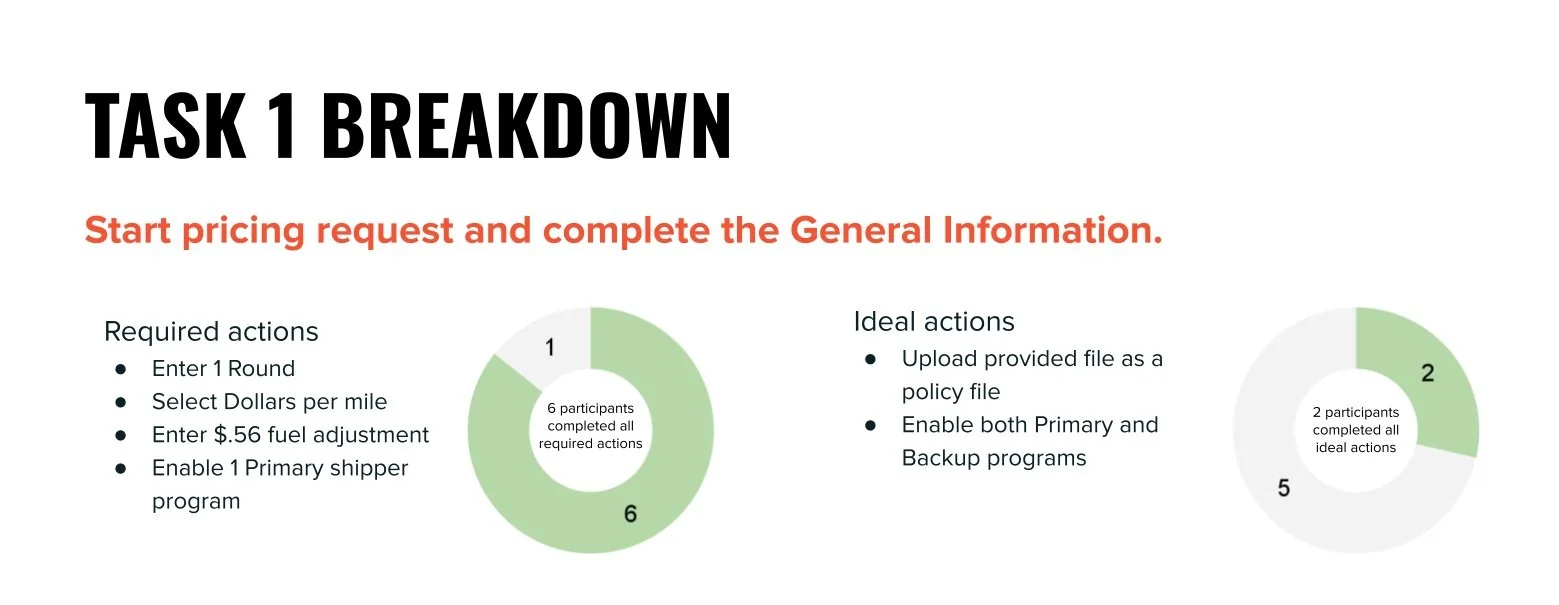

Nuance Within Task Success

It quickly became apparent that task success/failure was not a straightforward measurement. I met with the Product Manager, went through each task in detail, and had them decide on the minimum requirements for success for each task. Completion of minimum requirements would result in task success and count towards usability. Beyond the minimum requirements were a set of ideally completed actions, which would count towards measuring effectiveness of the product rather than task success. My reasoning behind this was that if the product was working at maximum effectiveness, then all users should be able to complete tasks in the ideal manner. In other words, effectiveness was a higher bar than usability. Throughout the study, there was a high occurrence of missed optional actions, which led to the another product principle. The product needed to give better guidance. Users should not be left unaware that the way they interacted with the product would cause problems later on in the process. The product should have better guidelines to help users know to how to use the product in the most effective way.

Project Impact

The attitudinal data from the usability study agreed with the beta testing group feedback, that this product was much better than the previous product and process. However, the study also uncovered many opportunities to improve the product’s user experience.

Building Empathy through Video Clips

When I presented the study findings to the team, rather than reviewing the prioritized list of product recommendations, I used a majority of my time to show video clips of participant sessions. I wanted to give the team the experience of seeing people use, or struggle to use, their product. When you are an expert on your product, it can be easy to forget or not fully comprehend the extent to which users will experience the product differently than you do. I wanted to increase the team’s empathy for the users and to give them the opportunity to see the need for product improvements firsthand.

The Value of a Usability Study

It was important to me to make the case for usability studies and show how the findings added new information beyond previous beta user feedback. I used the summary of study data and results to show how the most positive results all came from attitudinal data and the less positive results were all from behavioral data. This did not surprise me, because I expected to see effects of human biases that inflate attitudinal feedback, including the tendency for people to want to present themselves as competent and the tendency to want to please the team who built the product. I demonstrated that if the product team had only relied on the attitudinal feedback they received from the beta group, their perspective on the usability and effectiveness of the new product would have been skewed positively. The addition of behavioral data increased the rigor and reduced the bias of the existing product feedback.

Reflection

Choosing Level of Rigor

I chose to go deep on this study, collecting a lot of data and investing time and effort on analysis, presentation, and documentation. In being so thorough with this study, I was able to establish expectations of the value of usability studies. This set the stage for doing lighter-touch studies in the future, because I would have this project to point to as a demonstration. For a light-touch study I would condense the timeline, collect less data, but still be able to produce actionable insights for improving products.